An Introduction: Part 1 is here

Perhaps the biggest question in science is: What is the nature of human consciousness? This blog post doesn’t seek to resolve this issue but rather discusses known limitations in our models of consciousness and highlights the threats and opportunities of not knowing what consciousness is. Using the Scientific History of Mindfulness as a case study, this short article (and the subsequent series of postings) will illuminate a number of weaknesses in how the psychological sciences make sense of the world. In particular, the failure of psychology to recognise common mental processes essential to consciousness, such as nonduality. Not understanding how the mind works with duality/nonduality has been an extremely costly mistake in psychological research and practice. Limitations in current models of consciousness signpost potential problems in much of what we know about ourselves and those around us.

Put simply, consciousness is how you make sense of everything: awareness of yourself and the world around you. It’s what lets you think, feel, remember, and perceive. It includes your thoughts, emotions, sensations, and experiences. Each of us holds a different way of seeing the world. Think of consciousness as a self-generated prism through which we engage with everything. We share some perspectives with others around us, but each of us essentially has a unique view. If our view of the world is fundamentally distorted, it is because the prism through which we see the world is distorted. To many people, distortions can appear as truth, as objective reality, even when they are subjective. As individuals are also responsible for creating knowledge systems, such as psychology or physics, distortions in consciousness can bleed into ‘objective’ and ‘rational’ thinking.

In common with all academic disciplines, psychology is based on a series of beliefs about the world that are relative and partial; we call these beliefs ontology. As such, psychology can only offer ‘truths’ based on the rules of psychology rather than actual lived experience (although the two can often coincide). Knowledge that might fall outside empirical psychology, such as beliefs, emotional reasoning, subconscious mental processes or direct human experience, is often inaccessible to experimental psychology. Therefore, if we take the rules of science as ‘truth’, anything that does not conform to scientific norms has to be ignored, devalued or translated into scientific terms.

The idea that experimental processes are limited or flawed would present major problems for industrialised societies. So perhaps it’s not surprising that many traditional knowledge systems and religious concepts are disregarded by Western science, not because they don’t work but because science cannot evaluate them. Techniques from Traditional Chinese Medicine, such as acupuncture, are sometimes adopted by Western clinicians because they are effective. However, the technology is given low status because science cannot understand their underlying theoretical frameworks. In this way, vast swathes of human knowledge and techniques are dismissed because science just doesn’t have the tools to evaluate them.

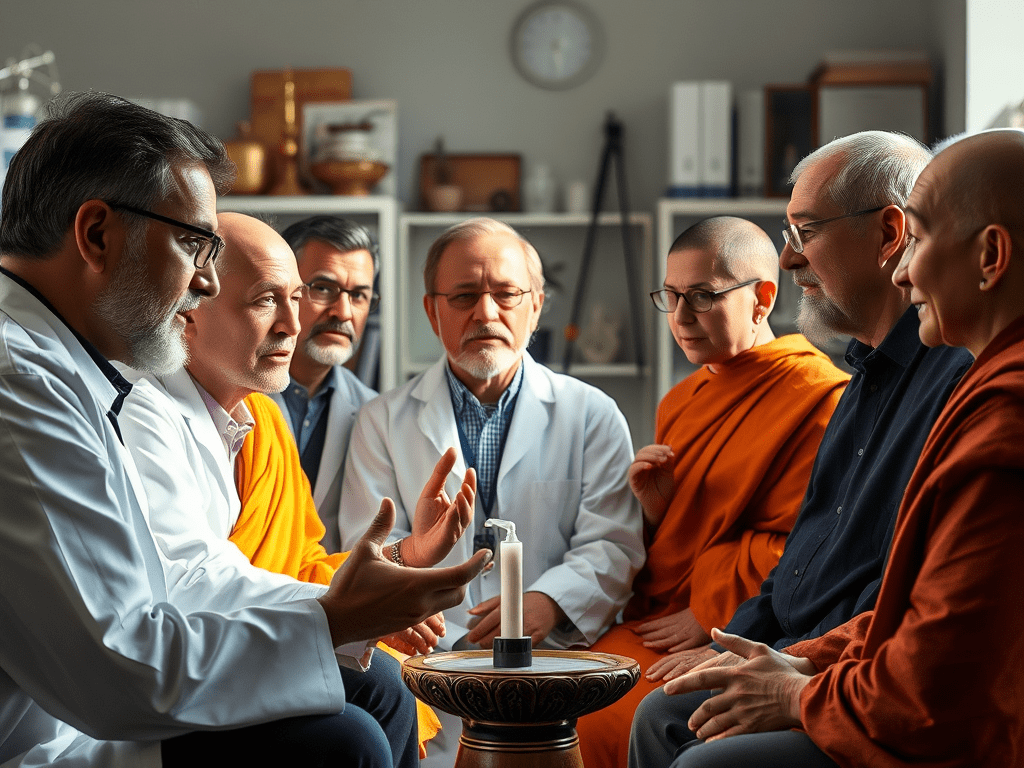

When you look at the scientific history of mindfulness from a transdisciplinary perspective, several problematic issues are visible in the way scientists treat religious knowledge in general and Buddhist knowledge in particular. By transdisciplinary, I am referring to an academic approach whereby we use all relevant knowledge to better understand what’s actually going on around us. Sometimes, a contrast in how different knowledge systems treat a behaviour, such as meditation, reveals the strengths and weaknesses of the respective systems. In the West, there is a convention that Buddhism is a belief system and, by contrast, the psychological sciences are a form of objective knowledge. Psychology is based on a belief (ontology), as is Buddhism. Science tests its hypotheses through a rational evaluation process, as does Buddhism. However, psychology is a dualistic system that creates dichotomies and artificial divisions that facilitate simplistic ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ conclusions, even to complex questions. Buddhist ontology, particularly in the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, is nondual, meaning it resists simple dichotomisation in favour of more inclusive understandings of mind and matter. The use of mindfulness in Buddhism is rooted in a sense of cause and effect. Ironically, in psychology, mindfulness experiments often rely on correlations rather than causality to explain the benefits of the practice.

The Buddhist concepts underpinning mindfulness are typically ignored or rejected by scientists, in part because psychological sciences are embedded in dualistic ways of knowing, whereas Buddhism tends to the nondual. A major problem for psychology is that human consciousness engages with dual and nondual awareness as well as the integration of both. A challenge in investigating consciousness is that we have to use consciousness to evaluate itself. If the ontologies used as the basis for the psychological sciences are nondual the product of experiments can only produce nondual insights, offering only partial understanding into the human condition. Scientists and clinicians began using religious knowledge and methods in the 1950s because of the healing potential of nondual insights. Over time, Western forms of meditation and mindfulness have removed these nondual elements because they cannot be seen or evaluated by empirical investigation. Science has failed to recognise that something profound (although abstract to dualistic investigation) is likely present in religious forms of meditation.

A crisis in Western mindfulness research identified a lack of scientific progress, despite 50 years of experiments costing billions of dollars. Yet almost no credible research has been undertaken to try to understand why the project has been relatively unsuccessful. However, because of the status of psychology in Western materialist societies, the transformed (nondual) nature of mindfulness is accepted as ‘truth’; even though the ontology of the psychological sciences reflects neither Buddhist knowledge nor the human condition. Without accepting limitations in the theoretical framework of psychology, we can expect the problems seen in the mindfulness project to be repeated. There is also little hope that dualistic approaches will ever be able to make sense of a human consciousness, which is, in part, nondual.

This is introduction to a series of posts which discuss, using mindfulness as a case study, the role of dual and nondual awareness in understanding the world around us. For Part 1 in the series click here.